Who would have thought that a tiny small square piece of stone, glass or pottery called tesserae would have such an important impact on culture and art history? As far back as the fourth millennium, on the walls of the Uruk in Mesopotamia, pieces of coloured stone cones were inlaid in a pattern, that bear a resemblance to mosaics. In the period of ancient history, more familiar to us though, the Greeks and pre-Christian Romans, enriched the floors of Hellenistic villas and Roman dwellings with magnificent mosaics. Mosaics were made almost always strictly for the rich, in painstaking detail, by the best artists of the day. Some of the most popular subjects for mosaics in ancient Greece and Rome were mythological scenes, daily life, the four seasons and the sea, the circus and gladiatorial games.

If I may indulge the reader for one moment, the Great Hunt Mosaic found in the Piazza Armerina, one of the grandest late Roman villas, is a wonderful example that illustrates a wide range of subjects. It is quite simply an eye-popping look at trade in the Roman Empire. Furthermore, if anyone is able to visit the Hatay Province, in Turkey, you will come across the important Antakya Archeological Museum. It has a rich collection of mosaics dating back to the second and third centuries with a wide-ranging display subjects, of which many are from the Roman and Byzantine period. Though, arguably the most famous and largest surviving Roman Mosaic worth studying is the Alexander Mosaic from the House of Faun at Pompeii. It is an exciting portrayal of Alexander The Great, in battle with Persian king Darius.

An important shift in mosaic art occurred during the early fourth century, one of a Christian nature. It is here that mosaics became more central to the life and culture of the Byzantines. I cannot hope to illustrate or cover every aspect of Byzantine mosaic art history here, but I will attempt to highlight some of the most interesting floor and wall mosaics that I have uncovered through my reading. It is the Byzantine master mosaicist that we are interested in for the purposes of this article. We arguably owe them a debt of gratitude for capturing scenes of history, everyday life, mythology, emperors, saints and much more! They primarily decorated and illuminated the churches of the Christian East between the fifth and fourteenth centuries. Much of what they created was destroyed through wars, conquests and controversy (iconoclasm), but enough of their creative brilliance survives in mosaics from across the old Byzantine world that absolutely overwhelms our senses on a grand scale.

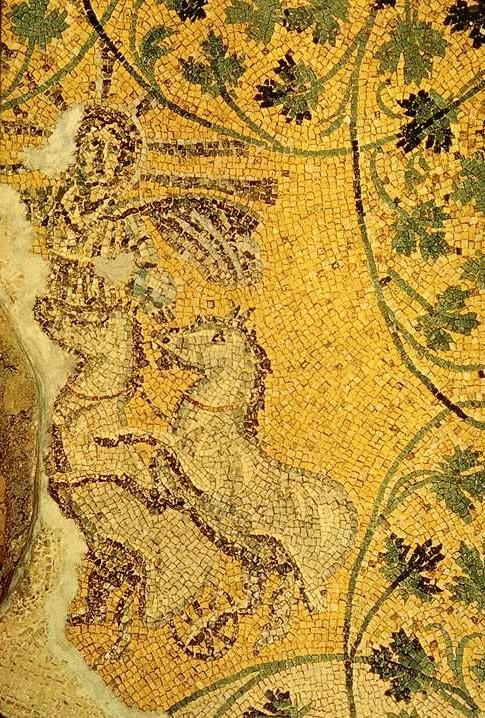

Christ as Helios

Before the reader starts jumping up and down, holding me in contempt for claiming the Christ as Helios as Byzantine, please calm down. I would merely like to highlight this interesting mosaic from the burial grotto of the Julii family, below St. Peter’s, in Rome, as one of the earliest surviving mosaic images of Christ. In an overtly pagan world, when this image was created, one where Christians in the mid-third century were still being persecuted, Christ is depicted here in the likeness of the pagan sun-god, Helios. It appears to have all the early typical elegance that Byzantine masters would employ later in open, despite the problems of identifying the true iconographic nature of this mosaic.

Two things in particular about the mosaic are interesting and important to me. The first is that Christ appears to be holding a blue globe in his left hand. This is an image that Byzantine emperors will be associated with, grasping an orb or globe in their left hand, as a sign of divinity or sovereignty. The second interesting aspect of the mosaic is its use of colour, primarily yellow or gold. I’m not sure that this mosaics glittering surface is meant to suggest gilded luxury, but Christ’s authoritativeness is nevertheless magnified. It is from around the third century that the introduction of gold glass tesserae revolutionized the possibilities of mosaics stunning effects. Gold would come to represent the ‘glory of God’ and Byzantine masters would exploit this decorative medium throughout their Byzantine church interiors.

Interior of the Aquileia Cathedral, Italy.

There must have been excitement amongst church leaders, when in the decades immediately after Constantine the Great and his co emperor Licinius, declared Christianity a legitimate religion in 313, that a number of new churches were built, as part of a grand new building programme. The cathedral of Aquileia was, in fact, one of those early new churches, built as a double-hall church. The massive open spaces running through the middle of the church, would have easily accommodated a large numbers of parishioners, who would have simply gazed in awe of the mosaic floor designed by the empire’s best craftsman. Interestingly, the mosaic floor is the only thing to survive from the original church, which was first destroyed by Attila the Hun. It was, of course, destroyed and rebuilt several more times over the centuries, until in 1031, Patriarch Poppo, used the site of the south hall to erect his new church. Today, we have him to thank for carefully preserving the original fourth century mosaic. It is an impressive floor mosaic that features stories of the Old Testament. There are no overtly Christian symbols, only a riot of animals and creatures. One of the most popular scenes on the floor of the cathedral is that of Jonah and the Sea Monster.

Christ as the Good Shepherd, Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna.

Many of the richest collections of Roman/Byzantine mosaics are found in Italy. The most famous of these mosaics are arguably found in the many churches of Ravenna. There you will find Justinian, the ‘poster boy’ of Byzantium (with his Ravenna mosaic plastered on more history book covers than any other) and his wife Theodore, suspended high on the walls of the San Vitale. We have no doubt that Justinian would have employed Greek-speaking artists and craftsmen, to tackle the intricate and painstaking details of his mosaic and a number of others too. The same could be arguably said of the mosaics commissioned in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, which appear to be also associated with Byzantine artistic achievement.

Magnificently suspended on the lunette over the north entrance, The Christ as the Good Shepherd, is one of the finest mosaics from the second quarter of the fifth century. In golden robes and with a golden halo and cross, Christ sits as a humble shepherd looking after his flock. Interestingly, Christ is beardless, a lot like the Christ as Helios mosaic. The illusionism of the mosaic is absolutely breathtaking and powerful.

Christ Pantocrator in the Monreale Cathedral, 12th century, Sicily.

The Cathedral of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary in Monreale is often regarded as one of the wonders of the medieval world. It is a Norman church that resembles a fortress with its two towers. Inside, however it resembles a glittering heaven, made up of gold mosaics, decorated by master Byzantine craftsmen, brought to Sicily from the Byzantine Empire by King William II.

It wasn’t uncommon for foreign rulers to employ Byzantine artists. For instances, the interior of Islamic religious buildings were sometimes painstakingly decorated by Byzantine mosaicists because of their great abilities and skills. Two examples that are often mentioned, where Byzantine mosaicists were employed are, the interiors of the Dome of the Rock (691) and the Great Mosque, Cordoba (965).

As visitors to Monreale enter the Cathedral, the long aisle focuses the visitor’s attention on one image in particular, the Christ Pantocrator. It is truly impressive as the arms of Christ extend across the apse to welcome the faithful. In short, it is quite typical of most images of the depiction of the Christ Pantocrator. He is holding the bible in his left hand, while his right hand is raised in blessing. He certainly gives the impression of being ‘the Ruler of all’.

Megalopsychia Hunt Mosaic, Daphne.

Sometimes by accident archeologists stumble across an important mosaic that reveals something far more interesting than just Christian motifs, and that is images of daily life in the empire. Evidence of this is found on the topographical border of the mosaic of Megalopsychia, that was once on a large villa floor, in the Roman town of Daphne, an ancient suburb of Antioch (Yatko). This mosaic is dated to about the second half of the fifth century and is a very good example that shows the development of Byzantine art and the influences upon it of Asiatic factors. It consists of a central medallion incorporating a beautiful image of Megalopsychia, surrounded by various hunting scenes, in which the whole mosaic is framed by a border of street scenes of the great city of Antioch.

The image that I have chosen to highlight daily life in Daphne, contains a scene showing what appears to be two men playing a dice game in a public space called the ‘covered walk’. Standing or sitting besides these two men is a vendor who is selling his goods from a table. Many more scenes like this show both buildings and daily life. Some of the highlights include a colourful portrait of local inhabitants or perhaps travellers, a forum or plaza, a workshop, the Olympic stadium of Antioch, the Great Church of Antioch and the Imperial palace. The badly damaged Megalopsychia mosaic is today displayed at the Antakya Archeological Museum, as a reminder to us all, of the painstaking skills of Byzantine craftsmen.

The Procession of Female Martyrs, Basilica of San Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna.

During the time of the Byzantine reconquest of the sixth century, General Belisarius made the city of Ravenna the capital of the exarchate that represented the distant Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in the West. It probably didn’t come as a surprise that under Justinian’s conquest of the city, Arian property would eventually be requisitioned, which included the Arian palace church of Theodoric. The Byzantines went about tearing down many of the reminders of its former ruler Theodoric the Great. (With an opposing belief that Christ was not fully divine, Arianism was never going to win its battle over the Orthodox Byzantines.) The north side of the nave of San Apollinare Nuovo is one of the best examples of the changes the Byzantines wanted to incorporate (c.560). Although it saw fit to keep much of the original Italian traditions of the mosaics on the nave of the church, obvious eastern influences were added, in particular a newly incorporated procession of female martyrs. It is believed that these female martyrs probably replaced the mosaic images of Theodoric and his court. In early church tradition, the procession was an important part of the Orthodox liturgy, and the fact that it has been replicated on the walls of the nave suggests artistic brilliance. (If I am correct in saying, this was a foreign artistic concept to the Roman West, one that obviously originated in the East?) Just simply look at the walking motion of the martyrs, which is faintly indicated by the lean of their cloaks and the dissymmetry of their veils.

Dome Mosaic of Church of the Rotunda, Thessaloniki.

Some art historians have said that the enormous richly decorated dome mosaics of the Church of the Rotunda, would have once felt heavenly in appearance during its day, before it was defaced and converted into a mosque by the Ottomans. It was originally built for Constantine the Great’s rival, Emperor Galerius (ruled 305-11) as a mausoleum. However, for whatever reason Galerius wasn’t buried there and the Rotunda stood empty for years until Constantine commissioned it to be built as a church. Its vast interior including the dome was subsequently decorated in mostly shimmering gold mosaics. Interestingly, Byzantine mosaicists’ used these early gold-ground mosaics to great effect, capitalizing on reflecting light, against the shimmering gold mosaics, that poured through the Rotunda’s windows. You may have to squint to see what appears to be four angels that surrounded the figure of Jesus Christ, suspended in the centre of the dome. Christ is unfortunately no more (only his left hand and halo remains), but it appears that Christ was probably positioned to look like he was holding up rings of rainbows, vines, pomegranates and apples and stars.

The Transfiguration, Monastery of St. Catherine, Mt Sinai.

In the Monastery of St. Catherine’s you will find many original sixth century Byzantine decorations. Among them on the upper part of the apse and the triumphal arch over the altar, you can find one of the most beautiful and refined of all Byzantine mosaics. That mosaic is the Transfiguration of Christ, which was made during the reign of Emperor Justinian. (Between the sixth and ninth centuries, the Monastery of St. Catherine’s was known as the Basilica of the Transfiguration, after the mosaic itself.) Its lavish style and painstakingly obvious craftsmanship is attributed to the work of artists from the imperial school in Constantinople. Though, if you look carefully at the mosaic, you will notice that even the most experienced Byzantine artists can make obvious mistakes, for instance, in the case of St. Peter’s two right feet!

The Transfiguration was likely commissioned in the remote part of Egypt to show the predominately Monophysite communities of Egypt, that Christ didn’t have just one nature, but two (Christ was both human and divine). The mosaic of the Transfiguration shows Christ standing within a blue mandorla, to make him stand out against the gold leaf background and from which miraculous and supernatural lights emerge. Importantly, he is accompanied by the figures of Moses, Elias and his closest disciplines, St. James, St. John and St. Peter, to whom he reveals his divinity.

Click HERE for Part 2 of this series.

Really beautiful pictures!

So beautiful and fascinating! Love to see more women’s Byzantine fashions!

https://historyisfascinating.wordpress.com/

Many thanks for the great article. I shared it on my Facebook mosaic page ( http://www.facebook.com/SoniaKingMosaicArtist ) I look forward to the next installment!

Wonderful. So much history is embedded in art! Wish I could go in person, but this is virtually as good.

Of all art, I like mosaics the best. I was in Ravenna many years ago and I still remember the wonder I felt looking at the magnificent work.